By Rich McLaughlin, Ph.D.

Professor Emeritus, North Carolina State University, Raleigh

ONE OF THE MOST basic approaches to capturing sediment in flowing water is to slow the water to allow the sediment to settle behind a barrier of some kind. Check dams (CDs) are commonly used for this purpose and to reduce erosion in the channel.

Check dams can be installed temporarily on construction sites, or permanently in typically steep terrain with high erosion rates. In 2024, a study of the latter application was conducted in a canyon in semi-arid southeastern Arizona,1 where a series of rock-masonry check dams had been constructed across the channel in the 1930s to control sediment coming from areas that lacked vegetation due to mismanagement.

The study surveyed the upper 18 CDs, which drained 11 ha (27 ac). All of the CDs, ranging from 2–15 m (6.5–49 ft) wide and 0.5–2.5 m (1.6–8 ft) high, were completely full of sediment, but there was no evidence of bypass or scour.

At seven of the CDs, researchers removed cores sampled at 10 cm (4 in) intervals to bedrock. The cores were used to estimate age (based on Cesium-137 deposited in 1963 from atomic bomb testing) and determine bulk density. Sediment volume was estimated for all 18 CDs.

For reasons including increased CD size and reduced channel slope, the majority of the captured sediment was in the CDs closer to the bottom of the canyon. The slope of the deposited material behind the CDs was 31%–79% less than the channel slope. Finer-textured material was captured at depth in the lower CDs, but not in those at higher elevations.

Based on isotopic analysis, many of the upper CDs had filled within 30 years, but the lower CDs filled later as estimated erosion rates increased, possibly due to a change in vegetation from grass to scrub. Technicians noted that the canyon’s CD spacing did not follow a standard design; the top of each lower dam was level with the toe of the one above it, reducing potential storage volume substantially.

Protecting Stormwater Drainage

Once stormwater drainage systems are installed on a construction site, they must be protected from heavy sediment loads until the area draining to them has been stabilized. Sites use many different devices to pool water around an inlet to settle the coarser parts of the sediment.

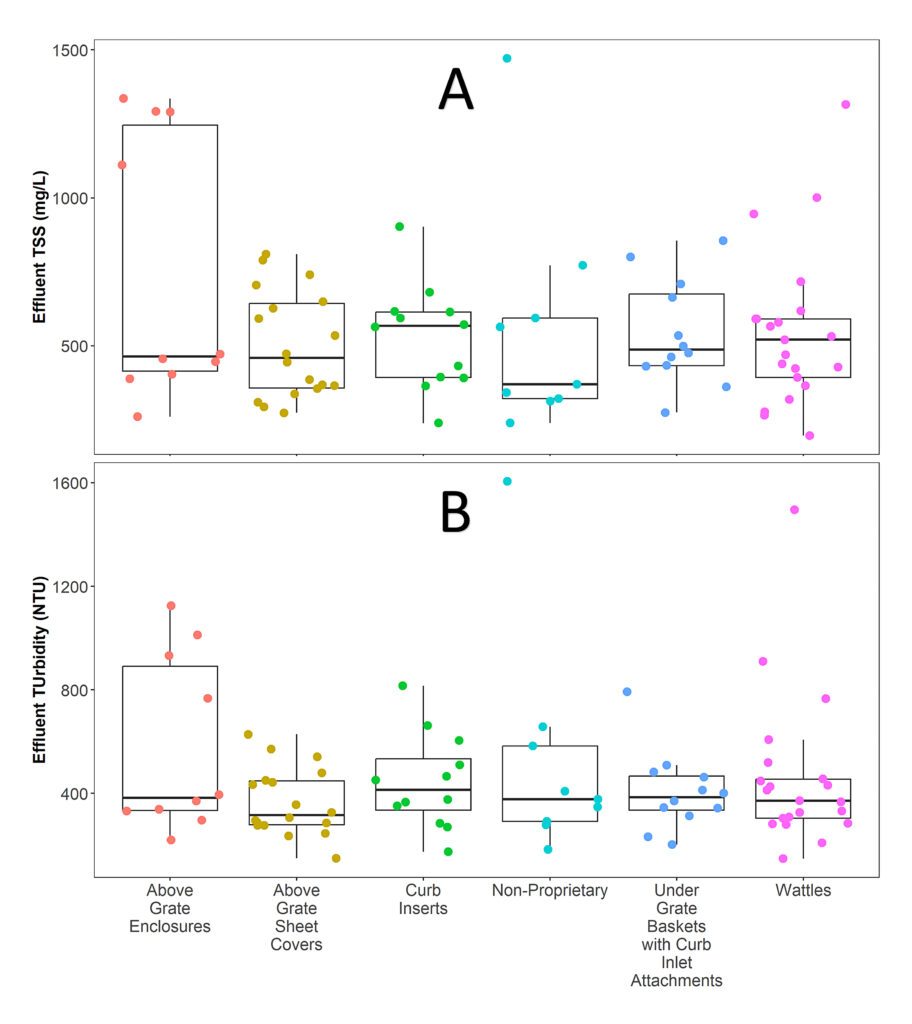

Researchers conducted a study in Ohio to compare three of these “standard” devices to 24 proprietary devices to evaluate reductions in sediment and turbidity.2 They constructed three types of storm drains typically used on roads, testing a grate only, a grate with a curb opening (overflow), and a curb opening alone. A concrete curb was installed on all three, but the roadway remained unpaved. They also built a bare-soil ditch that drained to an inlet for testing.

Chart created by A. Grimm

Devices included sheet covers on grates, above-grate enclosures, curb inserts, under-grate baskets, typical nonproprietary enclosures, and wattles as barriers. The simulated storm was 12 mm/h (0.5 in/h)—equivalent to a 10-year, 6-hour event for the area—for 30 minutes. Sediment was mixed into the water for a target of 800–1,200 mg/L and introduced into the road section or ditch as sheet flow.

Researchers tested each device in triplicate and cleaned all parts of the system thoroughly between tests. They then measured each device’s reduction in sediment and turbidity to evaluate its effectiveness in comparison to the others.

There were no differences in effectiveness among the devices, but reductions in sediment in the water ranged from 40% to 80%. Much of the variation revolved around design issues that allowed for bypass flow, especially under the devices or through gaps. Most devices did not pond water to the point of overflow, but those that did delivered no improvement in water quality compared to the others.

The nonproprietary barriers ponded water more than the others, suggesting that they should not be used where there is traffic. Effluent water quality improved, but likely still exceeded parameters for aquatic organisms; it would require further treatment to meet those values.

About the Expert

Rich McLaughlin, Ph.D., received a B.S. in natural resource management at Virginia Tech and studied soils and soil chemistry at Purdue University for his master’s degree and doctoral degree. He retired after 30 years as a professor and extension specialist in the Crop and Soil Sciences Department at North Carolina State University, where he specialized in erosion, sediment, and turbidity control. He remains involved with the department as professor emeritus.

References

- Polyakov, V., M. Nichols, and M. Cavanaugh. 2024. Determining sediment deposition dynamics influenced by check dams in a semi-arid mountainous watershed. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms, 49(6), 1849–1857. doi.org.prox.lib.ncsu.edu/10.1002/esp.5802

Grimm, A.G., R. A. Tirpak, J. A. Kerns, J. D. Witter, and R. J. Winston. 2024. Holistic evaluation of inlet protection devices for sediment control on construction sites. Journal of Environmental Management, 364,121256, ISSN 0301-4797, doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.121256