The escalating severity of wildfire seasons in California highlights the urgent need for effective land and water resource management. Fires in urban riverine systems can threaten lives and infrastructure while severely impacting stream health and stability; specifically, post-fire flooding and sediment transport can degrade essential drinking and recreational water sources. 1,2 While immediate post-fire impacts on surface hydrology such as sedimentation and flooding are well-documented, studies in semi-arid urban systems, where human activities significantly alter natural fire and hydrological regimes, remain limited. In addition to geomorphic changes that affect erosion control, water quality and sediment dynamics, urban fires can create additional strain on limited firefighting resources. This issue is exemplified by the 2018 California wildfire season, which required the simultaneous efforts of nearly 10,000 firefighters and the significant utilization of out-of-state resources.3

To effectively address post-fire geomorphic changes in urban streams, practical research-based insights into fire and vegetation management strategies are needed to support the development of resilient urban water systems. In 2024, the number of fires was within the five-year average, but the number of acres burned was over five times the average due to increases in flammable vegetation that spread fire. 4,5 In semi-arid urban stream systems in southern California, elevated year-round water levels contribute to increased nutrient loads and more frequent flash floods. These conditions encourage the infestation of flammable invasive vegetation, which alters erosion patterns and streambank stability. 6,7

The role of fire in riparian and wetland systems is not well understood, which may be due to the presumption that these habitats serve as barriers to fire due to high moisture content of soil and vegetation. However, flammable and invasive vegetation are making urban riparian systems prone to fire.8 For example, Arundo donax (giant reed) and Washingtonia spp. (desert fan palms) significantly increase fire fuel loads in urban riparian zones.9 Washingtonia filifera is native to isolated springs in the Sonoran Desert bioregion, while Washingtonia robusta is native to Baja California. Both species have spread from ornamental plantings and are known to influence fire regimes and become fire hazards as their populations increase. Giant reed is a large, bamboo-like grass from southern Eurasia that alters the diversity and function of riparian corridors throughout coastal California. Giant reed has fueled fires around urban areas and facilitated fire spread to natural areas; it inhibits post-fire recovery and can rapidly resprout from rhizomes. The rapid post-fire growth of giant reed contributes to an invasive grass-fire feedback cycle and further alters stream geomorphology.10,11 This cycle contributes to the increasing frequency of small urban fires (under 1,236 acres or 5 km2) in southern California4 and is exacerbated by human activity (i.e., power lines and recreational areas) near stream corridors.12 Dense vegetation, such as giant reed stands, also provides shelter for unhoused individuals, which has been associated with an increase in fire incidents. For example, the Los Angeles Fire Department reported that fires related to unhoused individuals nearly tripled in three years and accounted for 54% of their total fire responses.13

Historically, giant reed was introduced for erosion control along streambanks and ditches to increase stability.14 Almost 9,000 acres (36.42 km2) from Monterey to Mexico are infested with giant reed in southern California.15 The invasive species contributes to long-term trends of channel narrowing, channel bed aggradation and floodplain accretion.16,17,18 While removal of giant reed is recommended for riparian health, anticipating acute geomorphic changes from restoration is crucial for effective stream management in urban environments.

Pre- and Post-Fire Channel and Floodplain Dynamics

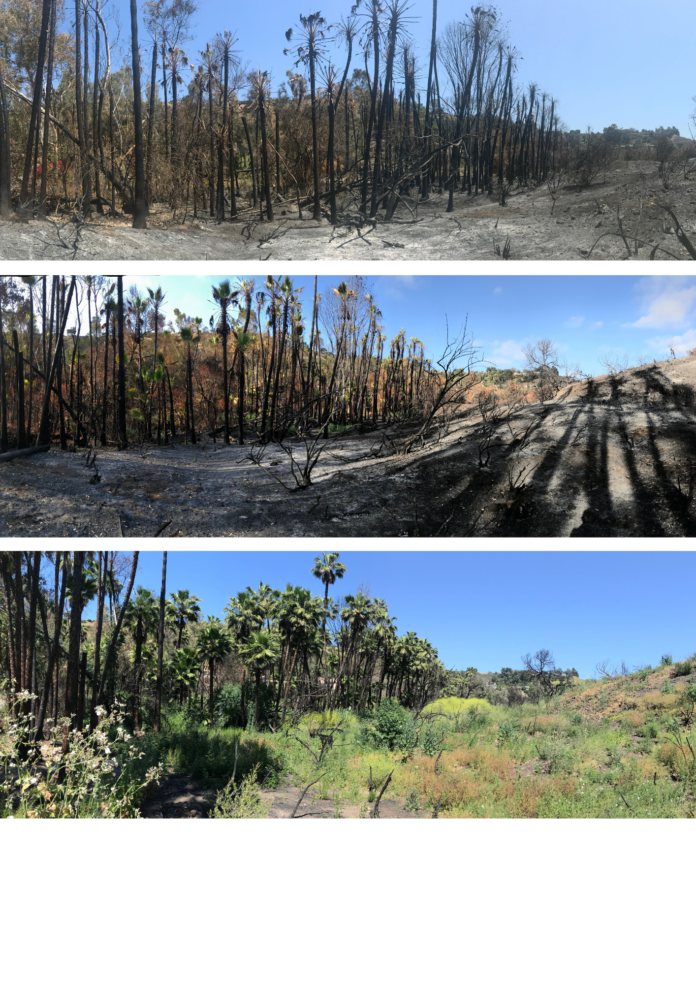

Alvarado Creek is an urban and perennial stream in San Diego, California, USA. The climatology is semi-arid and Mediterranean with warm, dry summers and cool, mild winters. There is substantial non-native vegetation in the riparian zones, which is representative of many urban riparian areas in the San Diego River watershed and many urban and coastal watersheds in southern California. A reach of Alvarado Creek was burned by a brush fire (Del Cerro Fire) on 3 June 2018 due to human ignition. Fueled by overgrown and invasive and flammable vegetation (giant reeds and palms), the fire burned 37 acres (0.15 km2). Rapid regrowth of giant reed was observed one week after the fire and dominated the landscape in subsequent years. Removal of burned and non-native vegetation occurred in fall 2020, which provided an opportunity to evaluate pre- and post-fire restoration. Additional herbicide treatment was applied to eradicate remaining giant reed roots and regrowth in fall 2021.

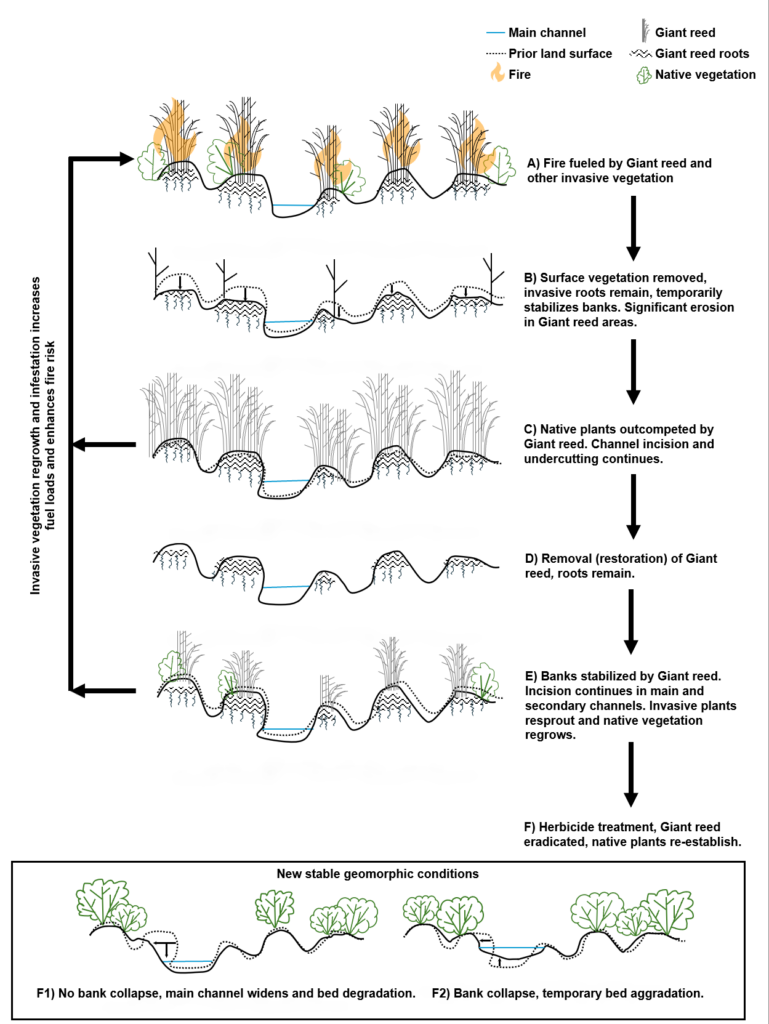

The giant reed significantly altered urban stream geomorphology both pre- and post-fire in Alvarado Creek. Before the fire, dense giant reed stands trapped sediment, forming berms and secondary channels, with accumulation rates comparable to those observed in much larger river systems.17 Although rapid regrowth of giant reed initially provided stability to upper streambanks after the Del Cerro Fire, the absence of native vegetation cover ultimately resulted in intensified bank undercutting, channel incision and significant floodplain erosion (Figure 1).

Channel and Flood Dynamics after Vegetation Management

Following the removal of giant reed, herbicide treatment resulted in further bank undercutting, collapse and overall channel widening. These observations demonstrate the substantial geomorphic disruption caused by the removal of giant reeds in smaller, urbanized streams, with retreat bank rates comparable to those in significantly larger systems.19 This disruption highlights the dual role of giant reeds in stabilizing and destabilizing streambanks. The rapid geomorphic changes triggered by the presence of giant reed, coupled with the lack of native vegetation and its abrupt removal, underscore the need for integrated erosion control strategies that account for the complex interplay between invasive vegetation species and stream dynamics (Figure 2).

The abrupt eradication of giant reed, particularly in post-fire urban waterways, triggers complex hydraulic, geomorphic and sedimentation responses that are understudied. However, as the Alvarado Creek recovers and native vegetation regrows, the geomorphic state has started to stabilize and gradually approach similar conditions to a nearby unburned, native vegetated site. Successful removal of the giant reed and subsequent native vegetation restoration may ultimately restore the natural geomorphic processes of the stream. Manual weeding and application of herbicide treatment can be used to control non-native vegetation and allow time for native vegetation to return. Also, a plant palette that reflects the local and native populations can be used to restore the native riparian conditions. In Alvarado Creek, seeds and cuttings were collected locally to ensure the genetic makeup and diversity were reflective of the native plant populations. This consisted of native willows, cottonwood and a variety of shrubs, grasses and wildflowers. We encourage future research to prioritize high-resolution modeling and at-risk area identification to develop optimized management strategies, which will benefit the long-term health and resilience of urban riparian ecosystems.

About the Experts

• Alicia M. Kinoshita, Ph.D., is an associate professor of civil engineering and director of undergraduate research at San Diego State University. She is an expert in short- and long-term watershed and hydrologic impacts of wildfire using remote sensing and field methods.

• Danielle S. Hunt graduated from San Diego State University with a Master of Science in civil engineering and a specialty in water resources. She is a design engineer at Stevens Cresto Engineers.

Acknowledgments

The material is based upon work supported by the Joint Fire Science Graduate Research Innovation (GRIN) Award No. 31-1-01-35, San Diego River Conservancy under Grants SDRG-P1-18-1, SDRG-P1-18-15, SDRG-P68-21-03 and SDRG-B22-05 and National Science

Foundation CAREER Program under Grant No. 1848577.

References

- White MD, Greer KA. 2006. The Effect of Watershed Urbanization on the Stream Hydrology and Riparian Vegetation of Los Peñasquitos Creek, California. Landscape and Urban Planning, 74:125-138.

- Stein ED, Brown JS, Hogue TS, et. al. 2012. Stormwater Contaminant Loading Following Southern California Wildfires. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 31:2625-2638.

- Federal Emergency Management Agency. 2018. State and Federal Partners Respond to the California Wildfires. Release Number: DR-4407-CA NR 002. fema. gov/press-release/20210318/state-and-federal-partnersrespond-california-wildfires.

- California Department of Forestry & Fire Protection. 2024 Fire Year. Outlook. fire.ca.gov/incidents.

- Karlamangla J. 2024. A Furious Start to California’s Fire Season. The New York Times, 11 July 2024, nytimes.com/2024/07/11/us/california-fire-season.html. Accessed 13 July 2024.

- D’Antonio CM. 2000. Fire, Plant Invasions, and Global Changes. In: Mooney HA, Hobbs RJ (eds). Invasive Species in a Changing World. Island Press, Washington, DC, pp. 65-93.

- Coffman GC. 2007. Factors Influencing Invasion of Giant Reed (Arundo Donax) in Riparian Ecosystems of Mediterranean-type Climate Regions. Doctoral dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles, CA.

- Drill S. 2018. Sustainable and Fire-Safe Landscapes: Achieving Wildfire Resistance and Environmental Health in the Wildland-Urban Interface. Fremontia, 38:37-41.

- Coffman GC, Ambrose RF, Rundel PW. 2010. Wildfire Promotes Dominance of Invasive Giant Reed (Arundo Donax) in Riparian Ecosystems. Biological Invasions, 12:2723-2734.

- Stover JE, Keller EA, Dudley TL, et. al. 2018. Fluvial Geomorphology, Root Distribution, and Tensile Strength of the Invasive Giant Reed, Arundo Donax and Its Role on Stream Bank Stability in the Santa Clara River, Southern California. Geosciences, 8:304.

- Mathews LEH, Kinoshita AM. 2020. Vegetation and Fluvial Geomorphology Dynamics After an Urban Fire. Geosciences, 10:317, doi:10.3390/geosciences10080317.

- Syphard AD, Keeley JE. 2015. Location, Timing and Extent of Wildfire Vary by Cause of Ignition. International Journal of Wildland Fire, doi: 10.1071/WF14024.

- Smith D, Queally J, Molina G. 2021. 24 Fires a Day: Surge in Flames at L.A. Homeless Encampments a Growing Crisis. Los Angeles Times, 5 May 2021, latimes.com/california/story/2021-05-12/surge-in-firesat-la-homeless-encampments-growing-crisis. Accessed: 13 July 2024.

- Bell G. 1998. Ecology and Management of Arundo Donax and Approaches to Riparian Habitat Restoration in Southern California. In: Brock JH, Wade W, Pysek P, et. al. (eds.). Plant Invasions. Backhuys Publishers, Leiden, The Netherlands.

- Giessow J, Casanova J, Leclerc R, et. al. 2011. Arundo Donax (Giant Reed): Distribution and Impact Report. State Water Resources Control Board Invasive Plant Council: California, pp.1-240.

- Allred TM, Schmidt JC. 1999. Channel Narrowing by Vertical Accretion Along the Green River Near Green River, Utah. Geological Society of America Bulletin, 111(12):1757-1772.

- Friedman JM, Vincent KR, Shafroth PB. 2005. Dating Floodplain Sediment Using Tree-ring Response to Burial. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms, 30:1077-1091.

- Dean DJ, Schmidt JC. 2011.The Role of Feedback Mechanisms in Historic Channel Changes of the Lower Rio Grande in the Big Bend Region. Geomorphology, 126:333-349.

- Pollen-Bankhead N, Simon A, Jaeger K, et. al. 2008. Destabilization of Streambanks by Removal of Invasive Species in Canyon de Chelly National Monument, Arizona. Geomorphology, 103:363-374.