Acid mine drainage (AMD) occurs when sulfide materials are exposed to oxygen and water, which causes acidic runoff.1 AMD can occur naturally but is mainly produced by mining activities, affecting vegetation, wildlife and water sources if untreated.2 Active treatment involves increasing the pH, which results in a metal hydroxide sludge. Disposal of AMD sludge presents management and environmental concerns due to the large area needed to store the waste, sludge properties (high water content and metal concentrations), and continuous sludge production even after mining activities end. This research evaluated

the potential for land application as part of the reclamation process by evaluating the use of AMD sludge as a soil amendment to support vegetation. This paper describes the results of a field test following one growing season.

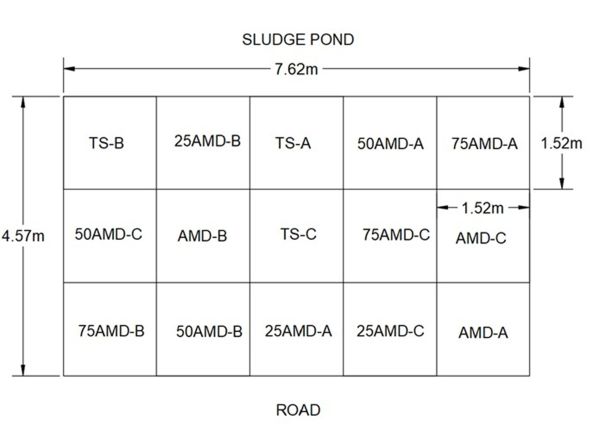

The study site was in Monongalia County, West Virginia, United States, at an elevation of 600 m (1,970 feet). Soil composition consisted of large rocks and sandy soil. During the time of this field test (1 May 2023 to 31 October 2023), average daily precipitation ranged

from 0.5 to 30 cm (0.20 to 12 inches), and average daily temperature ranged from 10 to 32 degrees Celsius (50 to 89.6 degrees Fahrenheit).3 Fifteen study plots, divided into three

repetitions of five treatments, were established (Figure 1):

- 25% AMD sludge/75% topsoil (25AMD)

- 50% AMD sludge/50% topsoil (50AMD)

- 75% AMD sludge/25% topsoil (75AMD)

- 100% AMD sludge (100AMD)

- 100% topsoil (TS, acting as a control).

Each plot, 1.52 m x 1.52 m (5 feet by 5 feet), was created by mixing AMD sludge, sourced directly from a geobag, with allpurpose topsoil in specified volumetric proportions. Following mixing, 0.575 pounds (260 g) of 10/10/10 N, P, K fertilizer and 0.034 pounds (15.4 g) of a seed mixture, including orchard grass (Dactylis glomerata, 48%), medium red clover (Trifolium pratense, 20%), climax timothy (Phleum pratense,12%), perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne, 8%), Kentucky bluegrass 85/80 (Poa pratensis, 8% and ladino clover (Trifolium repens, 4%), were applied.4 Straw was added after seeding (Figure 2). A soil analysis of each treatment is shown in Figure 3.

The AMD sludge originated from a treatment plant in Preston County, West Virginia. The treated sludge was pumped into a geobag and transported to the study site for final disposal. The AMD sludge was removed directly from the geobags.4

Two AMD sludge samples were characterized for metal concentrations (methods: EPA 6010D, EPA 7471B, SM 2540G-2015). The second sludge sample was collected after the first sample and resulted in a comparatively high concentration of lead (Figure 4). While there was variability between samples, arsenic, barium, chromium, lead, mercury and silver met basic requirements for land application according to the Rule of 20.5 The Rule of 20 is a guideline that is used to evaluate waste byproducts for land application based on their metal concentrations.5 Selenium concentrations for the sampled sludge were below detection limits; therefore, these concentration levels may require further evaluation.

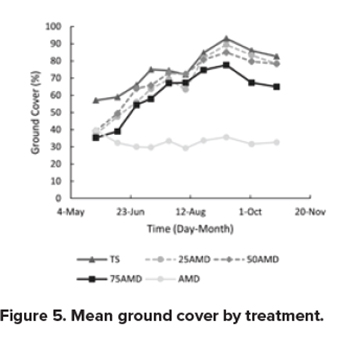

Ground cover was measured within each subplot using a 1 m2 (10.76 feet2) portable point frame and followed procedures by Coulloudon et al.6 and Elzinga et al.7 Measurements evaluated coverage by area of grass, straw and bare soil.

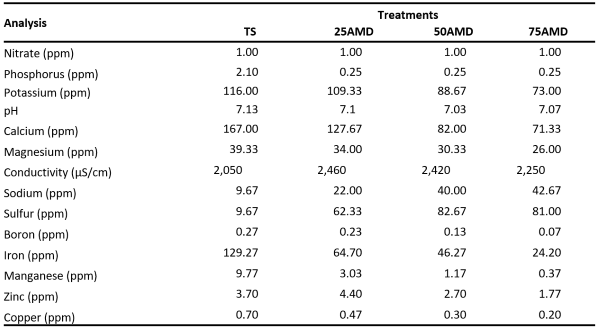

Soil moisture, electrical conductivity and soil temperature were measured with a soil at five randomly selected locations within each plot. At the end of the growing season, above-ground biomass and soil samples were collected by randomly placing a 0.09 m2 (1 foot²) PVC frame on each plot. The above-ground biomass in the enclosed area was trimmed, bagged and weighed. A soil sample, about 0.47 L (2 cups), was collected after removing roots and biomass. Soil samples were analyzed for nitrate, phosphorus, potassium, pH, calcium, magnesium, conductivity, sodium, sulfur, boron, iron, manganese, zinc and copper.

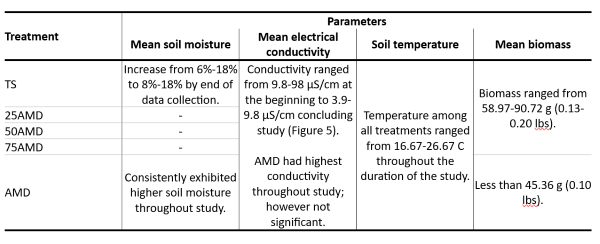

Mean ground cover in TS, 25AMD, 50AMD and 75AMD treatments increased from 30% to 60% at the start of the study to 60% to 80% by the end of the monitoring period (Figure 5, Figure 6). The National Pollutant Discharge System requires 70% ground cover for permit release.8 The study plots reached 70% cover after 13 weeks from planting. In contrast, the mean ground cover for the three AMD-only treatments remained below 40% throughout the study and was lower than the other treatments. Ground cover in the 75AMD treatment was consistently lower than in 25AMD and 50AMD. The TS treatment had the highest ground cover overall, with no significant differences compared to 25AMD and 50AMD. Figure 7 summarizes the results for mean soil moisture, electrical conductivity, temperature and biomass for each treatment.

The 100% top-soil plots had the highest constituent concentrations at the end of the study (Figure 7).

Conclusion

This research aimed to assess the use of AMD sludge as a soil amendment to promote vegetation growth. Key findings include:

The average ground cover for 100AMD was significantly lower compared to other treatments; therefore, this treatment is not suitable for vegetation establishment.

Soil moisture was significantly higher for 100AMD compared to other treatments, likely due to the 95% water content of the AMD sludge. Additional soil moisture within plots would support vegetation establishment, especially in the drier months. Future testing should consider drying the sludge before application for comparison.

Electrical conductivity was the highest in 100AMD treatment; however, the differences were not substantial.

AMD sludge has a high concentration of metals; however, the highest concentrations of iron, copper, manganese and zinc were shown in the topsoil (control) treatments.

These findings support the potential use of AMD sludge in reclaiming abandoned mine lands for vegetation restoration. Further research could explore future applications such as blending strategies, sludge site analysis and further treatment before application.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Grant/Cooperative Agreement Number S21AC10054 from the Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement (OSMRE). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of OSMRE. This work is with the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection, Office of Special Reclamation.

About the Experts

• Grace Kerr is a graduate research assistant at Auburn University.

• Leslie Hopkinson, Ph.D., is an associate professor at West Virginia University.

References

1. Akcil A, Koldas S. 2006. Acid Mine Drainage (AMD): Causes, Treatment and Case Studies. Journal of Cleaner Production, 14:1139-1145.

2. Ackman TE. 1982. Sludge Disposal from Acid Mine Drainage Treatment. Report of Investigations. PB-82-257148. Bureau of Mines, Pittsburgh Research Center.

3. National Centers for Environmental Information. ncei.noaa.gov.

4. Watters B. 2023. Exploring the Usage of Acid Mine Drainage Sludge as a Soil Amendment for Reclaimed Mine Lands. Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 11713, West Virginia University.

5. Davis S. 2001. Regulated Metals: The Rule of 20. Pollution Prevention Institute, Kansas Small Business Environmental Assistance Program.

6. Coulloudon B, Eshelman K, Gianola J, et al. Sampling Vegetation Attributes. 1999. BLM Technical Reference.

7. Elzinga CL, Salzer DW, Willoughby JW, et al. 1998. Measuring & Monitoring Plant Populations. BLM Technical Reference.

8. West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection. 2016. Erosion and Sediment Control Best Management Practice Manual. Division of Water and Waste Management.